Showing posts with label fashion culture. Show all posts

Showing posts with label fashion culture. Show all posts

Wednesday, 23 May 2012

The View from CPH

Iconic Hotel

Magasin - Department Store

Colour Combination

Window Display

Traditional Tailoring Shop

Designmuseum Danmark

Labels:

Copenhagen,

fashion,

Fashion Cities,

fashion culture

Wednesday, 1 February 2012

Fashioning the City RCA 2012

Getting ready to launch the Call for Papers CFP for the upcoming conference I'm organising at the Royal College of Art in September - Fashioning the City: Exploring Fashion Cultures, Structures and Systems.

For more info and to apply visit: www.fashioningthecity.wordpress.com

Labels:

ALCS,

conference,

fashion,

Fashion Cities,

fashion culture,

RCA

Tuesday, 8 March 2011

An Evening with Akiko Fukai

This evening I took the opportunity to head to the Japan Foundation in Russell Square, where Akiko Fukai, Chief Curator and Director of the Kyoto Costume Institute was speaking on the theme Japan/Fashion, followed by a Q&A discussion with Alison Moloney, Fashion Advisor at the British Council. In an introductory speech by the Japan Foundation's representatives we were informed that this was the very first time they had played host to a fashion event. Judging by the packed turnout of around 60 people in their seminar room, perhaps this will precipitate the start of more fashion-themed events to come. As the rest of the audience no doubt appreciated, this occasion offered the rare opportunity to hear from a curator working within a very different fashion and, indeed, curating culture.

Installation View Future Beauty: 30 Years of Japanese Fashion

In her brief presentation of around 20 minutes, Fukai gave us a whirlwind tour of Japanese fashion culture and its impact within Japan and beyond. Touching on the internationally recognised Japanese street style influenced by Manga, Anime, and ''kawaii'' or cuteness, Fukai also appraised the visible and invisible appropriation of Japanese aesthetics in Western culture. This ranged from the paintings of Van Gogh and Whistler, through to the ''deconstructed'' clothing of Ann Demeulmeester and Maison Martin Margiela. Through the development of Japanese designers influence on Paris fashion as showcased in the work of Hanae Mori, Kenzo, Issey Miyake, Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo, Fukai also unpacked the three core elements Japanese design has specifically had, namely textiles, silhouette and cutting or construction. In particular the stylistic form of the kimono has influenced the pattern cutting and ornamentation of such haute couture ''greats'' as Paul Poiret, Chanel and Madelaine Vionnet. Fukai also addressed the curation of her own recent exhibition ''Future Beauty: 30 Years of Japanese Fashion'', which recently ended at the Barbican and is now being exhibited at the Haus der Kunst in Munich. Through concentrating on the chief influencers on Japanese design internationally, namely Issey Miyake, Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto, together with a small selection of more recently established names, allowed Fukai to explore the key themes of the exhibition, including innovation and tradition in the use of textiles and silhouette, the flatness of cutting and pattern construction and the cooler, trendier aspects of ''kawaii''. As Fukai noted in her concluding comments perhaps one of the most important elements of Japanese fashion design, both in the last 30 years and today, is the ability of Japanese designers to explore and create through the co-existence of opposites, such as the seedy and the sublime, or nature versus the urban.

Jacket by Yohji Yamamoto

Following this overview of Japanese fashion culture Akiko Fukai was engaged in conversation with Alison Moloney, exploring further some of the questions raised in her talk. This conversation was extended with questions from the assembled audience. One of Fukai's key insights during this discussion was into fashion's changing status in being exhibited in art gallery context in Japan. Following similar developments in Europe, over the last ten years fashion, too, has begun to receive greater prominence in Japanese art galleries and museums, which Fukai put down not least to her own efforts and that of her colleagues at the Kyoto Costume Institute. In looking at the designers she had chosen for the recent Barbican/Haus Der Kunst exhibition, Fukai commented on how for her these designers did indeed represent Japan and Japanese-ness, even if the designer's themselves did not recognize their own work in that context. Fukai acknowledged that several Japanese designers see themselves and their work in a more rounded, international or global context, rather than as being specifically Japanese, which raises interesting questions regarding the local versus the international, or the exotic other versus the known. Further to this it was interesting to hear Fukai's thoughts on the changing fashion system, represented as she noted in the recent sacking of John Galliano by Christian Dior. As Fukai noted it used to be that recognition grew out of the talent and/or skill of individual designers, this was how Japanese designers grew to prominence during the 1970s and 1980s in Paris. During the late 1980s and 1990s, however, the power of merchandising and branding came to prominence. Today, Fukai noted how the system has changed again from the power of big name brands, to 'fast fashion''. leaving a large question mark over what will happen in the fashion industry of the future. As Fukai made clear, fast fashion needs to get its ''nourishment'' from somewhere, as it is unable to develop or recreate that for itself. As was noted by a member of the audience it appears fast fashion has won, as firms like Uniqlo grow ever larger, yet Yohji Yamamoto was recently forced into liquidation. Yet for Fukai this appeared to be too simplistic a notion, instead she asserted that perhaps the future of fashion lies in a ''return to basics'', with people deciding for themselves what they find comfortable to wear. This could be purchasing ''one off'' items, or customisation of existing clothing, yet also clothing that is easily affordable and obtainable is also included in this equation, including Uniqlo. Fukai cited their J+ tie-up with Jil Sander as a possible indicator of what the future might bring. In addition, Yohji Yamamoto is not yet totally obsolete, since his work is set to be explored and celebrated in an exhibition opening shortly at the V&A, which perhaps will help to inspire the next generation of designers attending Britain's fashion schools.

Shirt from J+ Uniqlo

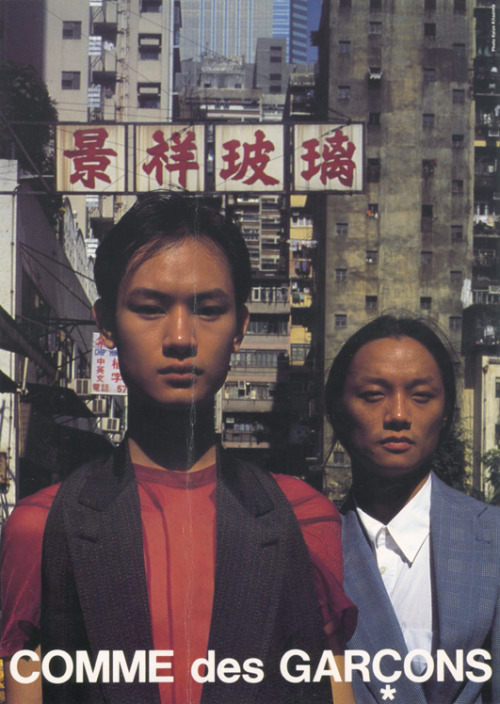

Overall, this was an interesting and lively debate in matters surrounding curation, identity, and the context and perceptions of a specific fashion culture. It will be interesting to see if the Japan Foundation decide to take this further in introducing a series of lively and topical debates on similar themes. But as for the burning question of the evening, who is Akiko Fukai's favourite designer? Well she was her own best ambassador, wearing an outfit by Comme des Garçons. As Fukai acquiesced, it is Rei Kawakubo's way of making her question that really appeals to her sensibility as a curator of fashion.

For further Information:

Kyoto Costume Institute: http://www.kci.or.jp/index.html?lang=en

Japan Foundation: http://www.jpf.org.uk/

Haus der Kunst, Munich: http://www.hausderkunst.de/

Tuesday, 16 November 2010

Who will it be - Jigsaw or Westwood? Galliano or Marshall?

Souvenirs at the ready...

After much speculation and anticipatory rumor Prince William and Kate Middleton have today announced their engagement. While much comment has been generated over the choice of ring (William's mother, Princess Diana's own engagement ring) the real speculation in fashion circles is what will the bride be wearing, and perhaps as importantly, who will be given the task of creating what will no doubt become one of the most photographed, blogged and tweeted upon dress of the century? As a former employee of mid-range brand Jigsaw it's not outside the realm of possibility that in these straightened times that Kate may choose something ''off-the-peg''. More likely, however, the task will go to a ''name'' British designer, perhaps some satin-silk ''picture-dress'' with a huge bustle by Vivienne Westwood? Or perhaps an intricately embroidered number by Matthew Williamson? Or even something spiky yet seductive by Gareth Pugh or Hannah Marshall? Although fully-resident in Paris, John Galliano has on hand the full might of the Dior ateliers at hand...and one can only imagine what Alexander McQueen could have created...or perhaps Christopher Bailey could develop something tasteful with a little Burberry-check...and of course she must wear a hat or headdress of some kind, British milliners are second-to-none, step forward Stephen Jones...

Coming on the heels of recent royal weddings in Sweden and the Netherlands, such a state occasion offers the opportunity for Britain now, too, on an even grander scale to assert its authority in the sartorial stakes of its official consorts. While the sartorial battles between the likes of Michelle Obama, Carla Bruni-Sarkozy and Samantha Cameron are well documented, the royal consort holds a special place in the demonstrating the cultural, and thereby political, superiority of nation states. Although the potency of their sartorial influence has perhaps waned under the plethora of actresses, TV and pop-stars that now act as fashion's ''role models'', the royal consort still adds a certain glamorous and exotic allure that their less-than-royal counterparts cannot hope to provide, or indeed compete with, as examples such as Queen Rania of Jordon prove. Yet the figure of Kate Middleton provides a new-take on the ''fairy-tale'' updated for the 21st Century, being a middle-class girl from a wealthy, self-made family. In dressing Middleton for her wedding the designer entrusted with the task will not only be creating a fabulous gown for a one-off occasion, they will also find themselves on duty to provide a dress that defines a new era in bringing the royal wedding into the 21st Century

Wednesday, 1 September 2010

New Shops: London

Colonisation, in a sense, can work both ways, particularly in the context of the exchange of fashion culture. While big name high-street and luxury brands are well-known to have the power and resources to open shops in far-flung destinations such as Dubai, China, Russia and India, brands from so-called ''developing'' countries are developing the resources and confidence in their product to do so too. In London, Turkish brand Desa, well-known for its leather heritage, is preparing to open, not one but two large stores, with one in Hampstead and a ''flagship'' in Covent Garden. Desa already operates 60 stores in its home market, plus a franchise operation in Saudi Arabia. Given the number of Middle Eastern visitors who like to spend their money on clothes in London, it would seem this is a canny move by the brand.

Advertisement by 7 For All Mankind

New denim stores are also set to open, with 7 For All Mankind, the ''original'' American premium denim brand, to open its first British store in Westbourne Grove. Dutch brand Denham, meanwhile, has turned its attentions to the East End, with the prospective opening of its third wholly-owned store in Shoreditch's Charlotte Road (the brand's other two concept stores are in Amsterdam and Tokyo). It appears as if each of these brands is taking advantage of favourable exchange rates, and a perhaps slight dip in rental prices, proving that even in a recession, London is still viewed as place of opportunity for fashion brands wishing to make their mark in this ''World Fashion City''. Having a presence in London, it seems, retains its caché.

Denham Jeans, look for the brand's ''scissor'' symbol

Since the ‘’explosion’’ of the Japanese designers in the late 1970s and early 1980s in Paris (names like Kenzo, Issey Miyake, Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto), there has since not been such a concentrated number of designers emanating from one place making a significant impact on the global fashion scene. From within Europe itself, perhaps only the ‘’Antwerp Six’’ can compare to this. Yet since the 1980s the nature of the fashion industry has perhaps changed considerably, with a larger amount of monetary resources needed to launch a fully-fledged fashion label to begin with, and also the development in technology, particularly, the Internet, meaning that connections between places are now much ‘’closer’’, taking away the need to travel to present collections before an international audience. Rather than a ‘’collective spirit’’ there also seems to be a move towards more designers striking out on their own, not necessarily setting up business in a ‘’World Fashion City’’ like London or Paris, but instead choosing to remain, or return to, their home town, building a local clientele before branching out abroad. It will be interesting to see if Desa is the first of many Turkish brands to begin on an international expansion, opening shops or franchises, especially as the country has built up a reputation for high-quality products, both ready-made clothes and textiles. For the European market, their proximity to the main Western European fashion markets of Germany, France, Italy, UK and Spain, mean many retailers are looking to source their own product from there, particularly in light of recent problems with deliveries from countries further away, such as India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Thailand.

Advertising Image by Vlisco

In a reversal of this, and perhaps reflecting the seemingly, almost ‘’circular’’ nature of the fashion industry, the Dutch firm Vlisco is little known in its home-market, yet it is a household brand across West Africa, famed for its intricately, brightly patterned batik prints, or ‘’Dutch Wax’’. Although, incidentally, some of its products can also be found in the less exotic confines of Brixton market, the best place to view the full range of its very luxurious products is in the firm’s flagship stores in Benin, Nigeria, Togo or the Ivory Coast. Vlisco certainly challenges the notion of so-called ‘’authentic’’ textile products, since these prints begin life in Helmond rather than Lomé.

Advertisement by 7 For All Mankind

New denim stores are also set to open, with 7 For All Mankind, the ''original'' American premium denim brand, to open its first British store in Westbourne Grove. Dutch brand Denham, meanwhile, has turned its attentions to the East End, with the prospective opening of its third wholly-owned store in Shoreditch's Charlotte Road (the brand's other two concept stores are in Amsterdam and Tokyo). It appears as if each of these brands is taking advantage of favourable exchange rates, and a perhaps slight dip in rental prices, proving that even in a recession, London is still viewed as place of opportunity for fashion brands wishing to make their mark in this ''World Fashion City''. Having a presence in London, it seems, retains its caché.

Denham Jeans, look for the brand's ''scissor'' symbol

Since the ‘’explosion’’ of the Japanese designers in the late 1970s and early 1980s in Paris (names like Kenzo, Issey Miyake, Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto), there has since not been such a concentrated number of designers emanating from one place making a significant impact on the global fashion scene. From within Europe itself, perhaps only the ‘’Antwerp Six’’ can compare to this. Yet since the 1980s the nature of the fashion industry has perhaps changed considerably, with a larger amount of monetary resources needed to launch a fully-fledged fashion label to begin with, and also the development in technology, particularly, the Internet, meaning that connections between places are now much ‘’closer’’, taking away the need to travel to present collections before an international audience. Rather than a ‘’collective spirit’’ there also seems to be a move towards more designers striking out on their own, not necessarily setting up business in a ‘’World Fashion City’’ like London or Paris, but instead choosing to remain, or return to, their home town, building a local clientele before branching out abroad. It will be interesting to see if Desa is the first of many Turkish brands to begin on an international expansion, opening shops or franchises, especially as the country has built up a reputation for high-quality products, both ready-made clothes and textiles. For the European market, their proximity to the main Western European fashion markets of Germany, France, Italy, UK and Spain, mean many retailers are looking to source their own product from there, particularly in light of recent problems with deliveries from countries further away, such as India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Thailand.

Advertising Image by Vlisco

In a reversal of this, and perhaps reflecting the seemingly, almost ‘’circular’’ nature of the fashion industry, the Dutch firm Vlisco is little known in its home-market, yet it is a household brand across West Africa, famed for its intricately, brightly patterned batik prints, or ‘’Dutch Wax’’. Although, incidentally, some of its products can also be found in the less exotic confines of Brixton market, the best place to view the full range of its very luxurious products is in the firm’s flagship stores in Benin, Nigeria, Togo or the Ivory Coast. Vlisco certainly challenges the notion of so-called ‘’authentic’’ textile products, since these prints begin life in Helmond rather than Lomé.

Labels:

7 For All Mankind,

Denham,

Desa,

fashion business,

fashion culture,

London,

shops,

Vlisco

Wednesday, 18 August 2010

New Books

As far as possible at the moment I am trying to make the best use of the books and materials I already have in my own ''library'', and also from those other free resources, such as the websites of newspapers and magazines (though the UK Times and Sunday Times websites are now subscription based, so I guess I'll be researching elsewhere from now on). Yet sometimes there are some books you just have to have your own copy of, as waiting for the library to get them in takes too long (besides, I tend to make a lot of pencil notations in my own books, something librarians tend to frown upon!). Aside from Magaret Maynard's book Out of Line: Australian Women and Style, published in 2001, there are very few publications on the Australian fashion scene, which is one of my potential case studies in my research into the Fashion City. So it was with great excitement that I came across this new publication from Thames & Hudson called Fashion: Australian and New Zealand Designers, by Mitchell Oakley Smith, an associate Editor at GQ Australia. While the book will probably not win any awards for its rather unimaginative title, the contents promise a good overview of Australian and New Zealand fashion designers who have emerged over the last two decades. The book covers some, now internationally well-known, stalwarts of the OZ/NZ fashion industry, profiling Akira, Alica McCall, Collette Dinnigan, Easton Person, Karen Walker, Nom*D, Zambesi, Willow and Sass & Bide. Lesser known names, at least to those of us in the Northern hemisphere, include Arnsdorf, Birthday Suit, Camilla and Marc, Dhini, Flamingo Sands, Lisa Ho, Pistols At Dawn, Something Else and Vanishing Elephant. Overall this book offers a visual treatise of the work of the profiled designers, together with a brief insight into their backgrounds and positioning within the Australian-New Zealand fashion scene. Similar to much of the world today, this particular fashion scene offers up a melting-pot of styles and influences, imbibed with a hard-working ethic on the part of the designers. As Oakley Smith states in his introduction:

The breakdown of the barrier that once existed between the secular fashion industry and the general public has been seen as the democratisation of fashion. Not detrimental to its growth or prestige, local fashion has gained attention, interest and, ultimately, respect of its public.

(Oakley Smith, 2010: pp xi)

It is interesting to note, however, that whatever recognition designers gain in their ''home-market'', it still remains necessary to for their reputations to be secured and confirmed outside of that of ''home market'', with catwalk shows and press coverage in the so-called ''first-tier'' Fashion Cities, such as Paris, London Milan and New York. This is something not limited to Australian and New Zealand designers, as even those based here in London have often not been recognised as leading talents in their field, in part because fashion is deemed ''too frivolous'', or because many British designers, particularly at the higher-end of the market, make the bulk of their income from exporting their work abroad.

The second book to enter my possession recently is the first look at the work of Alexander McQueen, subtitled Genius of a Generation, by Kristin Knox. Rather disappointingly this publication from A&C Black appears to have been a bit of a ''rush-job''. While up-to-date, including mention of McQueen's untimely recent death, the text offers only a rather superficial insight into the work of a man aptly labeled a ''genius''. Unlike many of his peers, McQueen was admired in part because he was perhaps one of the few, and perhaps last, designers to have served an ''apprenticeship'' in the traditional sense, working his way up from toiling away in the cutting rooms of Savile Row, to stints working with Romeo Gigli and Koji Tatsuno, and then an MA at Central St. Martin's, moving on to set up his own label, picking up the gig of Creative Director at Givenchy, and finally developing his own-name brand under the auspices of the PPR-owned Gucci Group. Amazingly, while his work has been exhibited in several fashion exhibitions, including the recent Zwart: Meesterlijk Zwart in Mode en Kostuum at MoMu in Antwerp, there has yet, as far as I am aware, to be a fully dedicated exhibition to McQueen and his truely outstanding contribution to fashion culture. The main plus-side of this book is the visual treatise it gives of McQueen's oeuvre, spanning his early collections up to the Autumn/Winter collection of 2010. As Knox references, while McQueen was sometimes dubbed a ''misogynist'' by the media, trussing up his models in masks, corsets and brutal looking jewellery, this rather misses the point, as looking closer, his collections can be viewed as providing a kind of modern ''armour'', aiding the confidence of a woman unafraid of facing the challenges of the contemporary world. It is a great shame for us that McQueen felt he was not able himself to continue producing work in the same confident manner he had so often delivered, yet I hope soon to view an exhibition of his work that is as celebratory and as challenging as his own catwalk presentations so often were.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)